Perspective

A Conversation with Anton Ginzburg

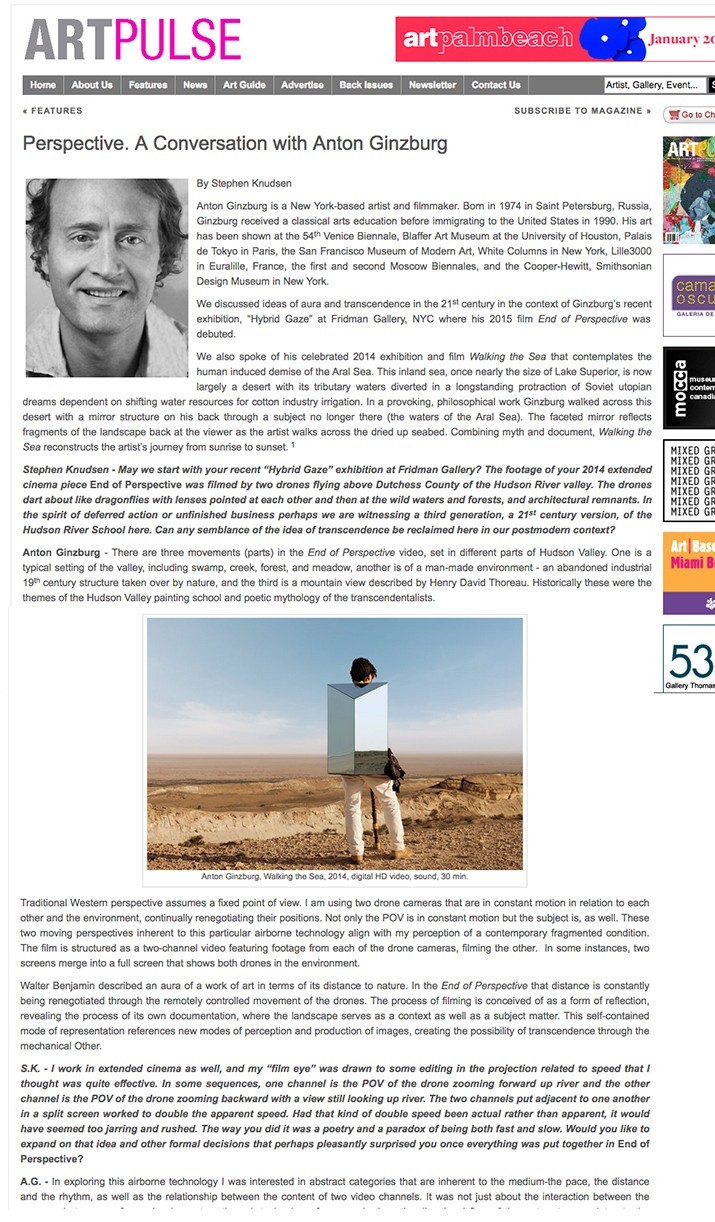

Anton Ginzburg is a New York–based artist and filmmaker. Born in 1974 in Saint Petersburg, Russia, Ginzburg received a classical arts education before immigrating to the United States in 1990. His art has been shown at the fifty-fourth Venice Biennale, Blaffer Art Museum at the University of Houston, Palais de Tokyo in Paris, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, White Columns in New York, Lille3000 in Euralille, France, the first and second Moscow Biennales, and the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York.

We discussed ideas of aura and transcendence in the 21st century in the context of Ginzburg’s recent exhibition, Hybrid Gaze at Fridman Gallery, NYC where his 2015 film End of Perspective was debuted.

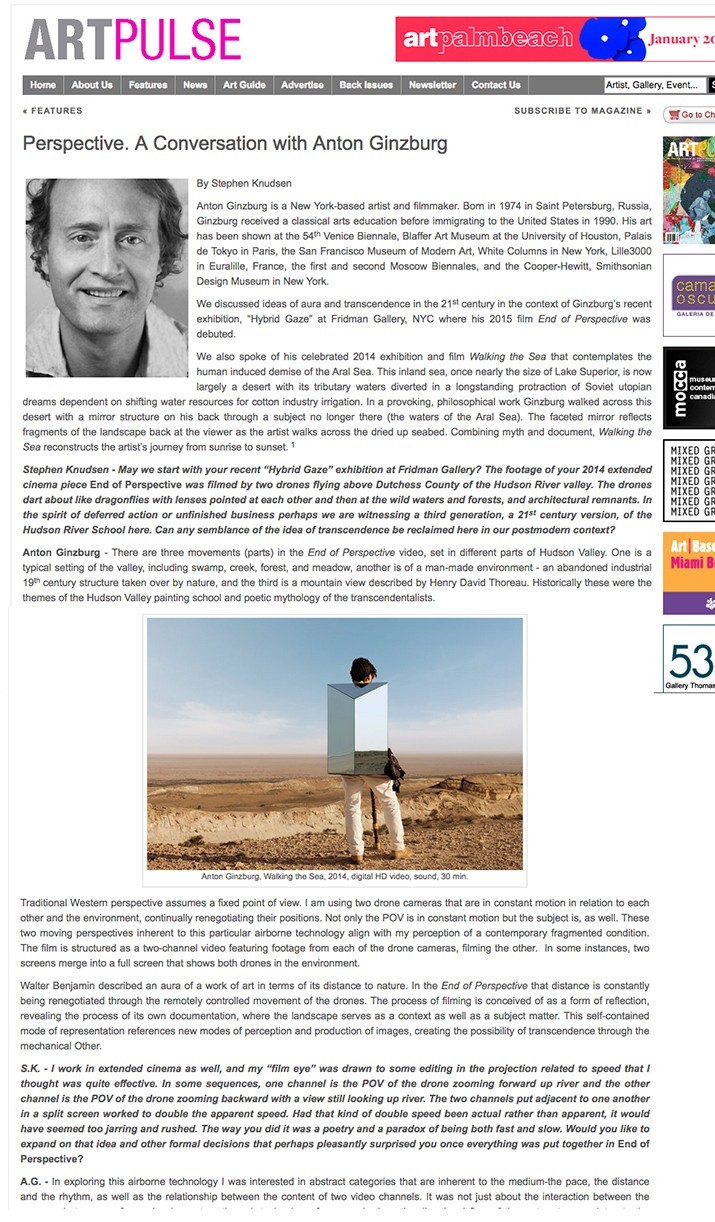

We also spoke of his celebrated 2014 exhibition and film Walking the Sea that contemplates the human induced demise of the Aral Sea. This inland sea, once nearly the size of Lake Superior, is now largely a desert with its tributary waters diverted in a longstanding protraction of Soviet utopian dreams dependent on shifting water resources for cotton industry irrigation. In a provoking, philosophical work Ginzburg walked across this desert with a mirror structure on his back through a subject no longer there (the waters of the Aral Sea). The faceted mirror reflects fragments of the landscape back at the viewer as the artist walks across the dried up seabed. Combining myth and document, Walking the Sea reconstructs the artist’s journey from sunrise to sunset.

Stephen Knudsen: May we start with your recent Hybrid Gaze exhibition at Fridman Gallery? The footage of your 2014 extended cinema piece End of Perspective was filmed by two drones flying above Dutchess County of the Hudson River valley. The drones dart about like dragonflies with lenses pointed at each other and then at the wild waters and forests, and architectural remnants. In the spirit of deferred action or unfinished business perhaps we are witnessing a third generation, a 21st century version, of the Hudson River School here. Can any semblance of the idea of transcendence be reclaimed here in our postmodern context?

Anton Ginzburg: There are three movements (parts) in the End of Perspective video, set in different parts of Hudson Valley. One is a typical setting of the valley, including swamp, creek, forest, and meadow, another is of a man-made environment – an abandoned industrial 19th century structure taken over by nature, and the third is a mountain view described by Henry David Thoreau. Historically these were the themes of the Hudson Valley painting school and poetic mythology of the transcendentalists.

Traditional Western perspective assumes a fixed point of view. I am using two drone cameras that are in constant motion in relation to each other and the environment, continually renegotiating their positions. Not only the POV is in constant motion but the subject is, as well. These two moving perspectives inherent to this particular airborne technology align with my perception of a contemporary fragmented condition. The film is structured as a two-channel video featuring footage from each of the drone cameras, filming the other. In some instances two screens merge into a full screen that shows both drones in the environment.

Walter Benjamin described an aura of a work of art in terms of its distance to nature. In the End of Perspective that distance is constantly being renegotiated through the remotely controlled movement of the drones. The process of filming is conceived of as a form of reflection, revealing the process of its own documentation, where the landscape serves as a context as well as a subject matter. This self-contained mode of representation references new modes of perception and production of images, creating the possibility of transcendence through the mechanical Other.

SK: I work in extended cinema as well, and my “film eye” was drawn to some editing in the projection related to speed that I thought was quite effective. In some sequences, one channel is the POV of the drone zooming forward up river and the other channel is the POV of the drone zooming backward with a view still looking up river. The two channels put adjacent to one another in a split screen worked to double the apparent speed. Had that kind of double speed been actual rather than apparent, it would have seemed too jarring and rushed. The way you did it was a poetry and a paradox of being both fast and slow. Would you like to expand on that idea and other formal decisions that perhaps pleasantly surprised you once everything was put together in End of Perspective?

AG: In exploring this airborne technology I was interested in abstract categories that are inherent to the medium – the pace, the distance and the rhythm, as well as the relationship between the content of two video channels. It was not just about the interaction between the cameras but a way of experiencing nature through technology, for example, how the directional flow of the water stream relates to the trajectory of the camera, producing tension and ambivalence between the medium and the message. I searched for an opportunity to reveal the invisible by deploying structural juxtaposition, what Robert Morris referred to as “sensation of relations” in sculpture. Perhaps it is a way of resurrecting an aura in the age of the Anthropocene.

SK: Yes, we have come a long way into the Antropocene, subverting the Hudson River vision with our Global Mischief, since Tomas Cole painted Oxbow, the 1836 quintessential Hudson River school painting. It is such a lovely image of pastoral humanity harmoniously coexisting with pristine nature. And a great part of that mischief has been in our relationship to images. In the 1980’s the late Vilem Flusser wrote of the technical image “where every event aims at the plenitude of our times, in which all actions and passions turn reaching the television or cinema screen or at becoming a photograph. The universe of technical images, as it is about to establish itself around us, poses itself in eternal repetition.” Flusser also said, “He no longer deciphers his own images, but lives in their function. Imagination has become hallucination.” Would you speak to this in relationship to your work?AG: As images turn into a technological stream they abandon their role as agents of imagination and instead take on a geological function as “technofossils.” The hybrid aura of technological and natural phenomena offers an interplay and a reconsideration of distinct perspectives, distances and spatial relationships. It brings to mind Jean-Luc Godard ‘s remark that, “a camera filming itself in a mirror would be the ultimate movie.”

The human body is absent from the End of Perspective and appears only indirectly through the process of recording and controlling the digital media. Identifying and mediating the gaze by means of montage is a strategy to resist mastery of vision over the subject.

SK: In the Hybrid Gaze exhibition, I was also caught by your uplifting challenge to some of the notions like decay of the aura in the age of mechanical reproduction in a piece titled AU01 . Would love to know what Walter Benjamin would say about your AU01 installation, the photo of an icon that you encountered on your recent trip to Sarajevo, that has been sanctified in a local church in 1971, thus installing an aura in this mechanical reproduction. Would you tell that story and the epiphany that you must have had with that image?

AG: When I was traveling to Sarajevo last summer I saw a photograph of an icon in a local antique store. When I turned it over I found a curious note – the photograph was sanctified in 1971. The traditional function of an Orthodox icon is not representation but generation of an aura. In this case, it meant that the aura that was lost through the act of mechanical reproduction was reclaimed through the ritual of sanctification. I thought it was an interesting unconscious illustration of Benjamin’s theory.AU01 installation was conceived as a deconstruction of this found artifact. The process of dilution and thickening of an aura was continued by employing digital technology. I produced two new artifacts – one by printing both sides of the icon photograph on glass and in this way floating the image in air. The other was generated by fragmenting and mapping the tonal values of the photograph as a relief. In the first case, I was taking away the physicality of the image, while in the other I concentrated on its materiality. The other part of an installation – the murals “AUTO” and “AURA”- engage language as an active agent reflecting the cyclical relationship or “rhymes” between the elements.

SK: Your work is also concerned with modernity’s planetary toll as well. In Walking the Sea, with split mirrors on your back you crossed the Aral Sea – an inland salt-water sea that lies between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Previously one of the four largest inland bodies of water in the world with an area of more than 26,000 sq. miles, the Aral Sea has steadily been transformed into a vast desert since the 1960s. This due to the Soviet irrigation project which diverted feeder-rivers to irrigate cotton fields in the surrounding desert.

Would you unpack the meaning of those mirrors that traveled with you and would you share an anecdote of the making of this work that perhaps you usually do not share?

AG: Walking the Sea, an exhibition, consisting of the film (of the same title) and sculptural installation was premiered at the Blaffer Art Museum at the University of Houston in 2014. It is a second part of the trilogy that I have been working on, which deals with post-Soviet geography. The Aral Sea was an important topic during Perestroika, the time when I was growing up in the Soviet Union. It was something that became impossible to ignore, the scale of the ecological disaster was so enormous that it became a subject of political consciousness. It was representative of the heroic modernist failures of the 20th century, an unplanned outcome of which was a paradox — a sea without water.

The existing environment is a result of human activity, realized on a geological scale. In thinking of how to represent the extent of this landscape and using Constructivist strategy of the “aesthetic of the fact”, I chose my body as a medium of representation. The narrative of the film is a walk – time and scale correlates to my body as a human metronome. I walked across the void of the sea with a mirror structure on my back as a way to map its different parts. The faceted mirror functioned as a camera in constant motion, incapable of recording. Because of its geometry, the structure reflects environment around, yet excludes the viewer. The mirror construction follows the logic of reverse perspective that switches the viewer and the viewed.

The Aral Sea is quite remote and difficult to gain access to, especially from the Uzbekistan side. The local officials avoid discussing the ghost limb of the missing sea. Traveling is strenuous and even though I managed to get the required permits to film, we were constantly harassed by local police and secret service trying to sabotage the project.

In one of the locations, my crew and I were arrested and detained at a local police precinct for a day, intimidating me and urging us to leave the area. Despite numerous challenges we managed to get rare footage of mostly inaccessible parts of the Aral Sea.

SK: Your film Walking the Sea is a particularly beautiful work. The mirror moving through the desert is quite stunning in a kind of Stanley Kubrick way. In one scene you walk far off in the distance to peer over a cliff. The mirror catches the sun and gives us just a flicker of sunset from the opposite horizon. The Kantian sublime (the cosmos) and the postmodern sublime (dynamical human power) seem to intersect at that moment. Would you further summarize your objective with moments like this and with Walking the Sea in general?

AG: I would like to cite a phrase attributed to Groucho Marx: ?Well, Art is Art, isn’t it? Still, on the other hand, water is water. And east is east and west is west and if you take cranberries and stew them like apple sauce they taste much more like prunes than rhubarb does. Now you tell me what you know.

Recalling Soviet amnesia required a sizable container. The emptiness of the sea seemed to fit that mission. My objective was not only to document the Soviet modernist project but also to observe my individual experience from an historical distance and to create a personal narrative. The locals believe that there is an inner sea underneath what used to be the Aral, so my walk was a form of unlicensed psychoanalysis, tapping into this geographical subconscious.

SK: In closing would you like to share the date and venue of your next exhibition?AG: There are several projects that I am currently working on.

I have been developing a public commission with a US-based organization “Art in Embassies”. It is a 24-feet stainless steel outdoor sculpture for the US Embassy in Moscow, called Stargaze: Orion. It was a conceptually challenging task, where I chose to approach the theme of the cosmos from a human point of view. Stargaze: Orion serves as an instrument, directing your gaze and framing the environment and constellations, rather than as an ideological object. The sculpture is set on a low black bronze pedestal that is an abstracted stellar map if viewed from above.

I also have an upcoming museum solo exhibition at the South Alberta Art Gallery (SAAG) in Canada in December 2016, called Blue Flame: Constructions and Initiatives. Exhibition explores collapse of the modern universalist project through formal investigations of Constructivist pedagogical experiments, combined with my personal mythologies. It culminates in Turo (“Tower” in Esperanto), a film exploring post-Soviet geography and Constructivist architecture. Modernity is interpreted as an updated Tower of Babel project that currently exists as an archive of ruins. Exploring various methods of representation, the video’s structure combines cinematic narrative, videogame footage and digital abstraction.

Loading ...

End of content

No more pages to load