Is Utopia Gone Forever?

Anton Ginzburg on the Lessons of the Soviet Art School VKhUTEMAS, and the Future of the Universalist Project

by Andrew Goldstein

https://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/qa/anton-ginzburg-interview-54600

For the past several years, the Russian-born, New York-based artist Anton Ginzburg has been working on a trilogy of films exploring post-Soviet geographies, searching for insights into the historical, intellectual, and cultural forces that have forged our contemporary reality.

His first cinematic journey, Hyperborea (2011), took him from the Pacific Northwest—where the American writer Washington Irving fancifully located the mythical land of Hyperborea—to Ginzburg’s birthplace of St. Petersburg to the northern gulags, where Russian archeologists claimed to have found evidence of the fabled domain. The second, Walking the Sea (2014), found the artist trekking by foot across the Aral Sea, an enormous former water body between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan that was entirely drained during Soviet times when the water was rerouted to irrigate cotton farms, creating one of the 20th century’s worst ecological tragedies.

Now, the third and final film has made its debut along with an accompanying exhibition at Canada’s Southern Alberta Art Gallery, and it shows the artist venturing further into his own biography, as a child of the Soviet cultural system. The show also happens to raise one of the most consequent questions of our time: what has happened to the utopian dream of a universalist world?

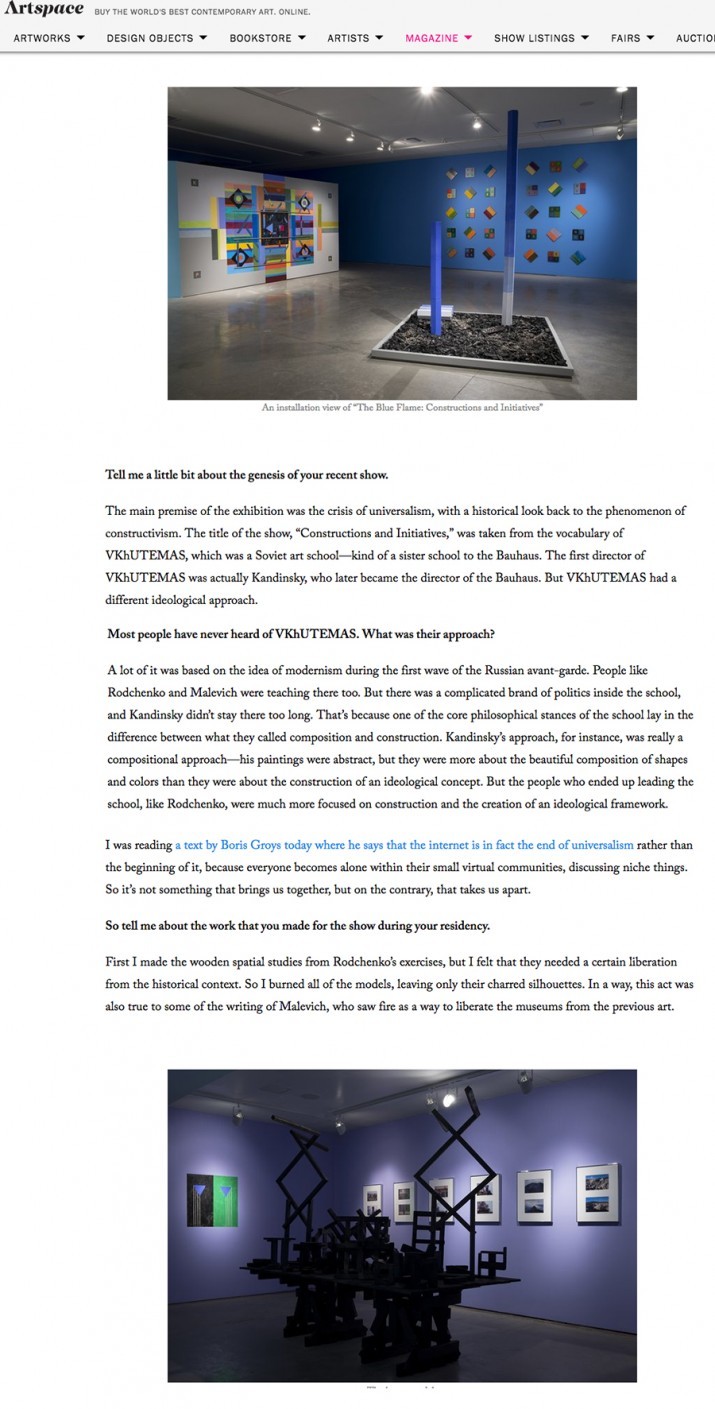

To delve into the concepts behind the exhibition, titled “The Blue Flame: Constructions and Initiatives,” Artspace’s Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Ginzburg about how he created the fascinating body of work, and what it has to do with the little-known Soviet art school—a cousin of the Bauhaus—known as VKhUTEMAS.

Tell me a little bit about the genesis of your recent show.

The main premise of the exhibition was the crisis of universalism, with a historical look back to the phenomenon of constructivism. The title of the show, “Constructions and Initiatives,” was taken from the vocabulary of VKhUTEMAS, which was a Soviet art school—kind of a sister school to the Bauhaus. The first director of VKhUTEMAS was actually Kandinsky, who later became the director of the Bauhaus. But VKhUTEMAS had a different ideological approach.

Most people have never heard of VKhUTEMAS. What was their approach?

A lot of it was based on the idea of modernism during the first wave of the Russian avant-garde. People like Rodchenko and Malevich were teaching there too. But there was a complicated brand of politics inside the school, and Kandinsky didn’t stay there too long. That’s because one of the core philosophical stances of the school lay in the difference between what they called composition and construction. Kandinsky’s approach, for instance, was really a compositional approach—his paintings were abstract, but they were more about the beautiful composition of shapes and colors than they were about the construction of an ideological concept. But the people who ended up leading the school, like Rodchenko, were much more focused on construction and the creation of an ideological framework.

What kind of ideology? Aside, obviously, from being communist.

It was an exciting project, really. A lot of the artists started their careers before the revolution, but after it occurred the revolutionary challenge in the Soviet Union was to create the new language, the new reality, for the new universalist, communist state. The constructivists and productionists were in charge of creating the reality to match the ideas. So the approach was very modernist, internationalist, and it was really a way to part with the sentiments of the previous art. This is why construction arose.

There were a lot of aesthetic and philosophical discussions about what construction is and what it means to architecture, drawing, and painting. According to Rodchenko, construction was “not just putting parts together, it is rather a deductive mode of generation. Nothing accidental, nothing not accounted for, nothing as a result of blind taste and aesthetic arbitrariness.” This faction believed art should be seemed in the ideas of Soviet communism. In fact, the “first slogan” of constructivism was “Down with speculative activity in artistic labor!”

To bring out another quote, another central thinker of VKhUTEMAS, Aleksei Gan, defined constructivism as “a communist expression of material constructions. It is a slender child of industrial culture.” His manifestos were extremely radical, saying, basically, death to art and down with all the sentiments—that the new art should not be a window but a hammer that creates a new reality. They wanted a really functional and forward-looking approach to art, getting rid of sentimentality and getting down to the construction of the new world.

So these were deeply utopian artists at VKhUTEMAS. Where did that leave Kandinsky and his compositional art?

Well, Kandinsky’s style was considered a kind of bourgeoise approach for VKhUTEMAS, full of superfluous elements. But this was quite fine for Bauhaus, and his style became one of the premises for the Bauhaus. There the ideology was less radical.

But he was too bourgeois for VKhUTEMAS?

Yeah, he was considered too bourgeois. I wouldn’t say he got kicked out, but he had to leave from being the head of the school.

How did you first become interested in VKhUTEMAS?

When I was growing up, studying art in the Soviet Union in the ‘80s, the avant garde was not necessarily welcome. It was too radical, and it was not part of the main art education, and it was not in public view in the museums. But still, I had some teachers who were aware of it, and would talk about it. Some people who had been students of VKhUTEMAS were also present, so the information was still accessible, and I was always very curious about it.

Later, when working on my trilogy, I realized my work shares a lot with Constructivist methodology, so I read some scholarly materials on the topic. Anna Bokov, for instance, is doing her PhD on VKhUTEMAS pedagogy at Yale. Her workshops on VKhUTEMAS Training, held as part of the Venice Architectural Biennale 2014, and on Rodchenko's Spatial Constructions and "Initiative" exercises and in particular, served as a source for portions of my exhibition. So I decided to go back to school, in a way, and experience VKhUTEMAS education.

What do you mean? How did you do that?

When I was approached by Southern Alberta Art Gallery curator Ryan Doherty to do a show there, he offered me a residency to prepare the work over the summer in the mountains of Southern Alberta, which is an absolutely breathtaking, beautiful landscape. They offered me a studio for a month and a half, with tools, and I knew I wanted to really dedicate myself to the exhibition and to put myself through a working process without actually knowing where it would end up—to approach it as a kind of experiment. So what I decided to do was put myself through the VKhUTEMAS curriculum, working through the different departments, and then have the result be the exhibition.

What do you mean by departments?

VKhUTEMAS had different departments—for example, it had a textile department, a woodwork department, and a metal department. It was similar to Bauhaus in that way, basically a number of models that the school had developed to explore how to work with space. Rodchenko also had designed “initiatives,” which is the term he used for technical exercises. I wanted to take this methodology of constructivism and to apply it to a current North American situation.

It’s amazing that you put yourself through the curriculum of this defunct revolutionary art school. How did you approach it?

I decided to do carpentry for two months in the mountains, absolutely alone. My day was dedicated to labor, where I would wake up, read the constructivist manifestos, do research on them, and then do carpentry following Rodchenko’s initiatives, building wooden models as part of his spatial studies. I also went through the curriculum of the graphic department, creating a series of posters for the show. I was exactly like a student, using this process to put myself in the universalist, revolutionary ideas of constructivism. A lot of the concepts and approaches and methodologies are still as relevant, even though the situation is different—the political situation, civilizational situation, historical.

You said before that you wanted to apply constructivism to the “current North American situation.” What do you mean by that? What connection do you see to the present day?

Well, I have to say it was an experiment for me. I wanted to see how I could work with current ideas, current materials, and current methods while staying true to this ideology—what would be the result? Politically, though, we’re in a very different situation. If you look back to the beginning of the 20th century, communism was really a universalist idea. It was an opportunity to unite the world, and this was reflected through the modern art that was sweeping all over the world and through initiatives of international language like Esperanto, which never took off. Now it appears that this dream of an international, universalist world is crumbling, with the rise of nationalism and the possible disintegration of the E.U.

I was reading a text by Boris Groys today where he says that the internet is in fact the end of universalism rather than the beginning of it, because everyone becomes alone within their small virtual communities, discussing niche things. So it’s not something that brings us together, but on the contrary, that takes us apart.

So tell me about the work that you made for the show during your residency.

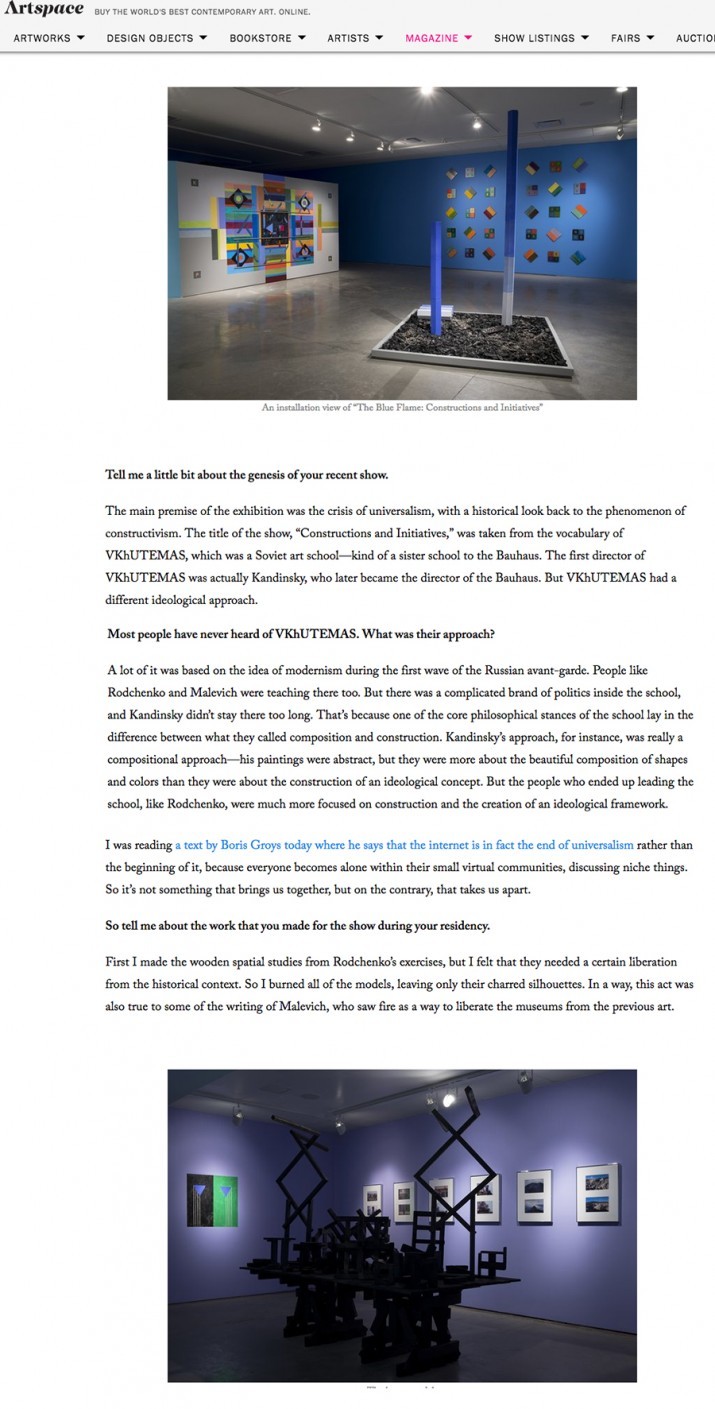

First I made the wooden spatial studies from Rodchenko’s exercises, but I felt that they needed a certain liberation from the historical context. So I burned all of the models, leaving only their charred silhouettes. In a way, this act was also true to some of the writing of Malevich, who saw fire as a way to liberate the museums from the previous art.

Liberate how?

Well, by burning the museums.

Malevich wanted to burn the museums?

Yeah, he wrote a text about it, about the liberation of art through fire. A lot of it was quite radical—but now, looking back at the 20th century, the constructivists themselves have become modern art history. So I felt the gesture of burning the exercises was true to their philosophy.

Tell me about the posters.

Graphic design visuals were very important because posters were a very important vehicle for constructivists. In the exhibition, it was a way for me to contextualize a lot of the ideas of constructivism, but also put it in relationship with history and also my own biography. I was exploring some of the ideas with El Lissitizky, for example, who was a member of the Yiddishism movement Kultur Lige, which was a Jewish modern movement that arose as an alternative to Zionist movement.

If Zionism was a religious project to return to the homeland in Israel, Yiddishism was instead really a celebration of Yiddish culture, and a way to bring Jewish culture into modernism, and modernism into Jewish culture. It was connected to the Bund movement, which was a Jewish socialist party, and it was a very different approach focusing on secular Jewish modernism.

And how many of the constructivists were Jewish?

The revolution helped to liberate a lot of Jewish people who, before that, were forced to live in the shetel. Since constructivism was an internationalist movement, it created an opportunity for these artists and architects to participate in a new project. In a way, it was a bit like the process of African-American liberation in the United States in the ‘60s, where the Jewish subject was liberated and given greater mobility in both the nation and the culture. It was like a big Jewish renaissance in Eastern Europe.

This is something I explore in the show with my film Turo—“tower” in Esperanto—which looks at four iconic constructivist buildings, several of which were built by Jewish architects. It starts with an ivory tower and goes to a control tower, which is part of Marshall McLuhan’s definition of modernism. So, I’m looking at modernism as new Tower of Babel that got destroyed.

What do you mean?

Well, I think the Tower of Babel was an effort to create a universalist project, but it was a failed attempt—all the languages got mixed and the tower never got completed. So looking at these iconic constructivist buildings is a way of reliving their creation as the first stage of a universalist project, now in the past, and as a way to imagine the future.

Kind of like retro-futurism.

Yeah, kind of like that. And it was actually very difficult to get access to these buildings, which are landmarks of Russian constructivism. The first building is Melnikov House, which is this amazing round structure with hexagonal windows. It was a very unique kind of building, initially a studio and a house for Melnikov—which was a really exceptional situation in the country, which had no private property. But, to repay his input for the Soviet Republic, he was given land and allowed to build a personal house. It’s like the ivory tower of Russian constructivism. So it starts with that, and luckily I was able to get access to it before the restoration.

What is the music in the film?

I collaborated with an incredible African-American Yiddish singer, Anthony Russell, and he sings a 1930s Yiddish song called "The City of the Future," in a way anticipating the construction of the buildings in which he performs. It’s superimposed over music by Wagner, which creates a kind of conceptual conflict.

How did you meet him? He sounds fascinating.

He is a really talented and well-known Yiddish singer, and when I first heard him sing I was very excited and I wanted to talk with him about collaborating. He was very well aware of the traditions of the Jewish subjects in tsarist Russia before the revolution and after revolution, and he proposed to perform this song.

What is the second building in the film?

Many of the constructivist buildings were never actually created—they only existed as plans, as ideas, as unrealized projects. One of these was Tatlin’s Tower of the Third International, which was never built. I was thinking how I could include the unbuilt tower in my film, and a very dystopian video game called Counter Strike, which takes place Eastern Europe, particularly in Chernobyl and in Pripyat, which was an ideal Soviet modernist city.

So what I did was I positioned a three-dimensional model of Tatlin’s Tower inside the video game and then filmed myself exploring it in ghost mode, meaning it doesn’t have any players and we’re just reviewing the modernist landscape, with a John Cage soundtrack "In the Landscape." So, by placing this unrealized project within this disturbing video game, it became a utopian project within a dystopian project. But eventually, in the film, the tower falls apart.

What about the film's third building?

So the third one is the Narkomfin Building, which is a landmark of constructivism. It was really expressing the ideology of the time. For example, it was called a “house commune,” so none of the apartments had a kitchen, which was a form of women’s liberation—there was a communal kitchen and kindergarten where people would have meals, meaning that women were liberated from being alone in the kitchen. If you look at architecture as a stage, it was really an enactment of the communist ideal. What I decided to do in this building is to put the first model of a theremin inside, because electronic music was a very important part of the development of early Soviet aesthetics.

Really, electronic music?

Yes. The first synthesizers were being developed then. There was even an incredible performance where a piece of music was played by factories, where an entire industrial town became the musical instrument, with each factory playing a different kind of “Woo woo!” sound in coordination.

Wow.

Finally, the fourth location is a very curious building. It’s called ZIL and it’s kind of a Soviet Detroit, in a way. It was an automobile factory that produced trucks, and tanks. The building itself is a beautiful expression of constructivism designed by the Vesnin brothers, with these long horizontal glass façades that go on for miles. Actually, this area is being redeveloped, so the footage I shot is very unique. A week later bulldozers came in and destroyed the buildings. But the amazing coincidence is that while I was filming it a fire broke out in the factory, so I have this very dramatic footage of the destruction of this constructivist architectural icon of universalism.

The destruction of the universalist project, as expressed by constructivism, is a pretty downbeat theme. Can you explain a bit further why you found this to be such a relevant topic?

I think it was my reaction to what’s happening in the world right now, which is kind of a crisis of universalism that is happening across Europe, that happened with the election in the United States. The universalist project is in crisis—communism as a project had a crisis at the end of the 20th century, and liberalism is having a crisis right now. I felt it was important to review the recent past in order to deal with the present.

What did you glean from putting yourself in the shoes of a kind of utopian art student from the 1920s?

For me, professionally as an artist, it was a way to acknowledge certain practices and methodologies that I shared with VKhUTEMAS. A lot of the education that I received in the Soviet Union still had elements of it, in a way. So it was a way to experience it directly without falling into the trap of stylizing. I wanted to answer the question, “What is a contemporary construction?”

What is a contemporary construction?

It’s a question of how to work with a context, how to work with materiality, how to express the self within the contemporary condition, apart from the ideology.

It was interesting what you said about Boris Groys earlier, because many people imagined that the internet would be a conduit for the universal ideal. Like, the European Union is crumbling, but at the same time Facebook is ascendant, creating a virtually interconnected online society. What hope do you think there is for the universalist project?

I think it’s very relevant, and I would like to believe in it. I would like to believe in a certain kind of universalist human experience that can be achieved through art, you know? But it needs to be rethought, it needs to be restrategized, it needs to be approached in a new way.

If the constructivist methodology was meant to reflect the ethos of its time, what do you think is the art form or expression that reflects the current moment?

Well, what I think was characteristic to the art of the beginning of the 20th century was a certain unity to the point of view, and a unity of ideology—at least, that’s the way we see from the perspective of today. Now, the world is much more fragmented. I think artists are afraid of a big statement, because a big statement will alienate certain groups of people. You cannot make a big statement without offending somebody, you know? And I believe art should be able to hit the nerve. Art, for me, is a way of generating knowledge.

As we saw with Trump during the election, it’s very possible for someone with an extreme, grandiose position to galvanize an enormous audience.

It’s true, but if you ask me, “What’s the problem with society?” I really see a huge problem in the mass desire for entertainment and consumption in all aspects of life. Everything needs to be entertainment, even politics, even religion. And I totally understand the impulse, but it’s very strange that everything in the capitalist culture needs to be an entertainment. We avoid thinking about things, feeling things. Everything becomes a form of mass capitalist consumer culture. For me, that’s really problematic, and needs to be overcome.