Pursued by a Cloud

by Andrew Goldstein

https://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/123784/pursued-by-a-cloud

"I need to know where to get mammoth tusks in St. Petersburg," Anton Ginzburg says into his cell phone, pacing around his airy studio in New York’s Flatiron District. "OK, OK, OK. Let’s do that." It is mid February, a few months before the artist’s most ambitious work to date is to debut in Venice during the city’s 54th Biennale, and Ginzburg is coordinating a staggering army of components and collaborators — Russian antiquarian shops, medical technicians, cinematographers, demolition experts — in cities around the world. The multipart artwork, documenting a search for the mythical paradise of Hyperborea, is being assembled for display in the Renaissance Palazzo Bollani alongside the art world’s most nation-oriented fair, but is appearing as a personal project of the 37-year-old Russian-born New Yorker, not for any country’s pavilion. Called "At the Back of the North Wind," it will combine the ancient with the ultramodern, static sculpture with windswept video, and political flash points with a defiantly apolitical stance. For Ginzburg, these contrasts are important because, he says, he is interested "in the impossible."

Hyperborea is a good place to go looking for the impossible since it probably never existed. The Greeks used this name to denote an imagined land far north of Thrace — believed to be the home of Boreas, god of the north wind — where the offspring of Apollo lived blissful thousand-year lives. It was written about by ancient poets and writers like Herodotus, who held it to be in what is now Siberia, and later embraced by a variety of mystics and pranksters and the odd hopeful explorer. In the 19th century, Theosophy founder Madame Blavatsky and her St. Petersburg circle claimed that the Hyperboreans were one of the world’s seven "root races." Washington Irving, that great American alternative historian and wit, fancifully located Hyperborea in Astoria, Oregon, a trading outpost founded in 1811 after an expedition bankrolled by John Jacob Astor. Today researchers are still seeking proof of this Shangri-la; Russian archeologists are now investigating sites near Kem and on the Solovki islands in the White Sea, near former Soviet gulags.

"What draws me to Hyperborea is that, to me, it’s really a metaphor for a very poetic state," says Ginzburg, who first became acquainted with the romance of northern exploration at St. Petersburg’s Museum of Arctic and Antarctic, close to his boyhood school. "But it’s also a dark paradox. In the search for utopia in the 20th century, all the revolutions turned completely into something else. The idea for the Communist revolution was really building this paradise on earth, but instead of building the paradise they kept themselves busy building prisons." An expat with precise manners, whose studio bookshelves overflow with art history, theory, and literature from around the world, Ginzburg came to New York as a teenager during the twilight years of the USSR, attended Parsons, the New School for Design, and put down roots. He has exhibited artworks ranging from sculpture and light pieces to installations and painting both in America — at White Columns and SFMOMA, for instance — and in Europe, in such venues as the Moscow Biennale and the Palais de Tokyo and on the façade of a building in Lille, France, where he created a spectacular display of generic Soviet-era store signs for items like bread and clothes topped by a glowing Medusa head. Now for his Venice project — which is being sponsored by the University of Houston’s Blaffer Art Museum, the Flo Art Fund, and Artpace San Antonio — the artist has merged the two halves of his background through a continent-hopping journey to rediscover Hyperborea. "The idea that somebody would go and try to find the physical proof, National Enquirer-style, that something actually existed seems a little bit absurd," he says. "But I was interested to see what else I would find on the trip."

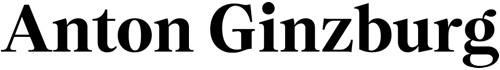

Ginzburg filmed his itinerary from Astoria, where wolves and owls preside over primordial, virgin woodland, to St. Petersburg, with its crumbling palaces and impeccable natural-history museums, to the twinned gulag and archeological sites in the White Sea. In the footage, the artist carries an early 20th-century surveyor’s tripod to chart his course, and he is followed everywhere by a ghostly cloud of red smoke, a symbol both of creative and emotional energy, in Jung’s cosmology, and of "a kind of collective unconscious that you can’t control but goes with the wind that carries across all the continents," says Ginzburg. In one particularly beautiful scene, the camera follows him as he walks across the frozen Neva River toward the State Hermitage Museum and is overtaken by a voluptuous billow of smoke that swells larger and larger as it travels around him before finally dissolving into pink mist against the building’s broad exterior. The shooting of the sequence involved something of a miracle: The artist flew into Moscow on January 24, the day of the terrorist bombing of Domodedovo Airport, "with two bags full of pyro for the red cloud," he remembers. "We had clearance, but it was very complicated." Later the crew needed a police escort.

The film provides the narrative for the exhibition at Palazzo Bollani, where it will be surrounded by artworks "that all have cameos in the film," according to the artist. The most spectacular, "Ashnest," consists of the mammoth tusks fused with long, sinuous polycarbonate segments — crafted using a 3-D printer to fabricate forms the artist created by manipulating the fragments of human bone on a computer — and suspended from metal supports over a thick black bed of coal, bronze residue, ash, and resin. The result is a "fictitious memory," Ginzburg says, that recalls the frozen displays at the St. Petersburg natural-history museums in the film. Other pieces include abstract paintings of maps, owl-headed sculptures of Carrara marble that are made from another human-bone scan (and recall Brancusi or Jean Arp), and a reconstruction of a Minimalist or Suprematist cube-shaped stack of shipping pallets Ginzburg found on a dock in Astoria. The red smoke, the film’s most memorable motif, is represented only by its echo in the cinders of "Ashnest."

The color of that smoke plus the film’s imagery of the gulag — stark yet painterly scenes of the ruined prisons, as well as former army barracks — and the artist’s own history with both the Soviet Union and the U.S. might lead some viewers to read a Russian political dimension into the exhibition. "Definitely not," Ginzburg says. "That was not my intention." Although he is represented by GMG Gallery in Moscow and was shown in ARCO’s recent Focus Russia section, devoted mainly to artists who still work and live in that country, Ginzburg is clear about his artistic profile. "I don’t consider myself a Russian artist," he says. "I think the whole notion of a national identity is dated. I think also recently it’s been such a speculative thing in contemporary art, and I have no patience for that. I find it very insincere, personally. For me, my career is really in New York."

This stance, together with the scale and determined complexity of "At the Back of the North Wind," should set the exhibition apart from the crowd during the teeming Biennale. And that is the point. "The fact that my project is being done in Venice as an independent project and not a national project is important to me," Ginzburg says. "For me it was an opportunity to experience the collective unconscious through the personal, the individual journey. We can view the reality as a group in a social context or as an individual. So for me probably it’s perception from the individual point of view, but something that everyone can experience."

"Pursued by a Cloud" originally appeared in the May 2011 issue of Modern Painters.